*Spoilers*

The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With The Sea by Yukio Mishima is a romantic book. There is beauty in it. It is concerned with glory, what it means to be a man and the search for meaning in a modern world which leaves no room for great causes. Yet at the same time it includes the darker, wilder, even barbarous elements which often accompany romanticism.

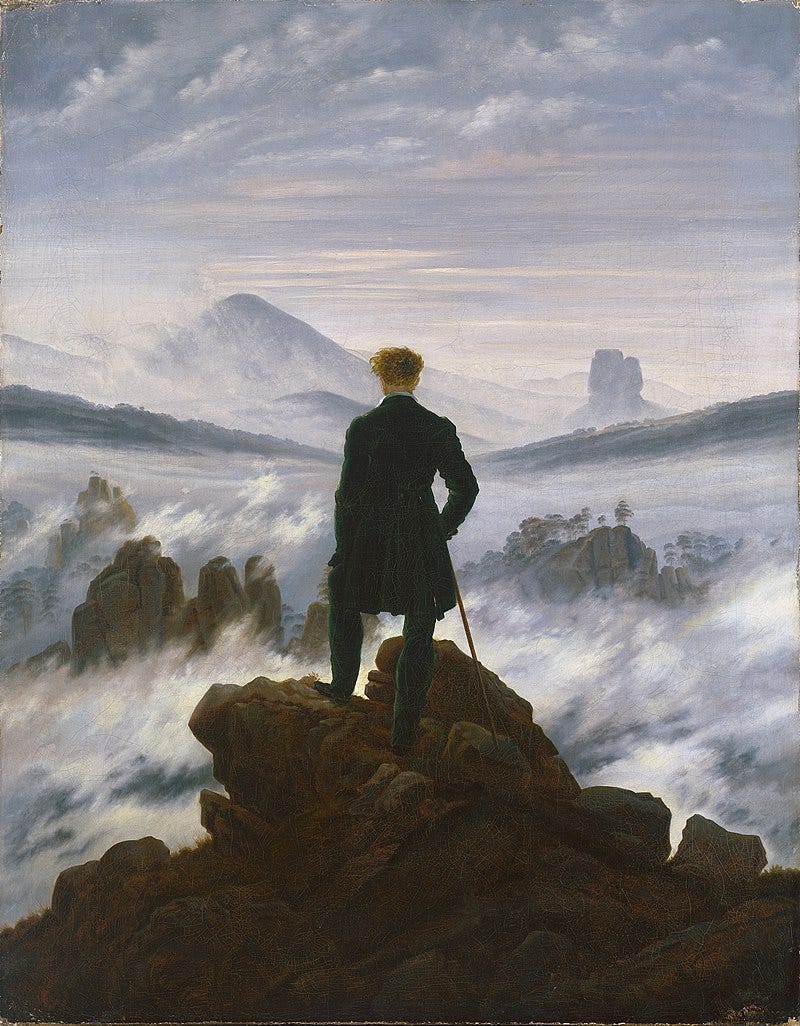

The central adult figure is that of Ryuji, a sailor. He has a longing for glory and what goes with glory in the romantic imagination, death. In this way Ryuji is a relatively familiar figure. He imagines himself as a great individual like the Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (Figure 2), the painting by Caspar David Friedrich, and belongs to the romantic strain which has as its icon Lord Byron dying a youthful death in the fetid swamps of Missolonghi in the service of the noble cause of Greek independence. Ryuji feels he is yet to achieve his destiny, although he is certain he has one. He says to himself, “a limpid, lonely horn is going to trumpet through the dawn someday, and a turgid cloud laced with light will sweep down, and the poignant voice of glory will call me from the distance”. Ryuji has been waiting for this and this is why he has never married. Yet at the start of the story he becomes involved with a woman named Fusako through her nautically obsessed son, Noboru.

Ultimately Ryuji decides to give up his romantic dreams and his life at sea to live with Fusako. This has a dramatic effect on Noboru, who is not your average thirteen-year-old boy. He is part of a gang who have rather peculiar and developed philosophical ideas which they feel mark them out as geniuses. They search for an internal order in a world they believe to be empty. They view the world of maturity and adulthood as petty, and they have a Freudian hatred of father figures. Noboru finds meaning in dramatic, significant moments such as when he watches his mother and Ryuji together and hears the call of a far-off ship or when Ryuji and Fusako part on the dock. Most shockingly, the group finds meaning in the killing and dissection of a kitten.

The book then takes an even darker turn, prefigured in the killing of the kitten. When the gang hears that Ryuji has given up life at sea and the way of heroism, they decide the only way to redeem him is to murder him. Ryuji himself has thought of death as a natural part of the glorious life. Now he is given the death he for a long time sought, but thought had passed him by.

In a barbaric way he has what he once wanted. The irony of this is conveyed in the last sentence in which Mishima confuses the taste of the drugged drink Ryuji has been given with the taste of glory itself: “still immersed in his dream, he drank down the tepid tea, it tasted bitter. Glory, as anyone knows, is bitter stuff”. Romanticism is often dark and wild and primal, it after all gave us vampires and gothic horror, but this seems too brutal. Ryuji was certainly a romantic, but the gang seem darker and more nihilistic. This said, both they and Ryuji do seem to be responding to the same problem: a feeling of emptiness in the world.

This lack of opportunity for glory and of great causes in the modern world is something Mishima also lamented elsewhere in his writing and ultimately he found his own cause in the shape of ultranationalism. This provided him with a context in which he could become a martyr by committing seppuku on the 25th November 1970 at a military base following his attempt to incite soldiers to rebel in the cause of Japan’s dignity and the supremacy of the Emperor. Ryuji is of course a much more attractive character than the boys and it is tempting to see in him Mishima’s actual ideas. However, Mishima is too subtle for one character to simply ventriloquise him and, uncomfortable as it is, on one reading, the last sentence does seem to convey the idea that Ryuji’s murder is consistent with true glory.

Before reading The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With The Sea I had coincidently been reading George Orwell’s Keep The Aspidistra Flying. Orwell would not have had time for a lot of Mishima’s ideas, in particular his paramilitary organisation, his uniforms and his worship of death, yet, reading these two books next to each other there does seem an interesting parallel. Like Ryuji and in a different way Noboru, Orwell’s Gordon Comstock dreams of a nobler life outside the mainstream. In his case this means a literary life not in service to the “money god”. Like Ryuji, Comstock decides to settle down and give up romantic dreams. For him this entails going back to his job in advertising and buying an aspidistra, the symbol of middle-class respectability. Would Comstock be redeemed if he were run down by car or murdered by a band of pubescent rascals, as happens to Ryuji? The comparison is to a large extent a superficial one. However, both books can be read as admonishments to the world that in modern life the romantic path is not more practical. What can be seen in Mishima’s book is that this civilisational failing may lead to an emptiness which is filled with arcane forms of barbarism. Ryuji’s romanticism is infinitely more appealing than the brutish philosophy of Noboru and his gang. In the case of Orwell’s book the barbarous alternative is more mundane and can be read in the jingles and slogans of the New Albion advertising company. Orwell’s look at an attempt to live a literary life is satirical. He knew too much about what the frugal life of a struggling author was actually like to view it very romantically yet Gordon Comstock’s failure to live such a life is sad. In this he identifies a similar problem with modern life, or indeed life, to the one Mishima writes about.