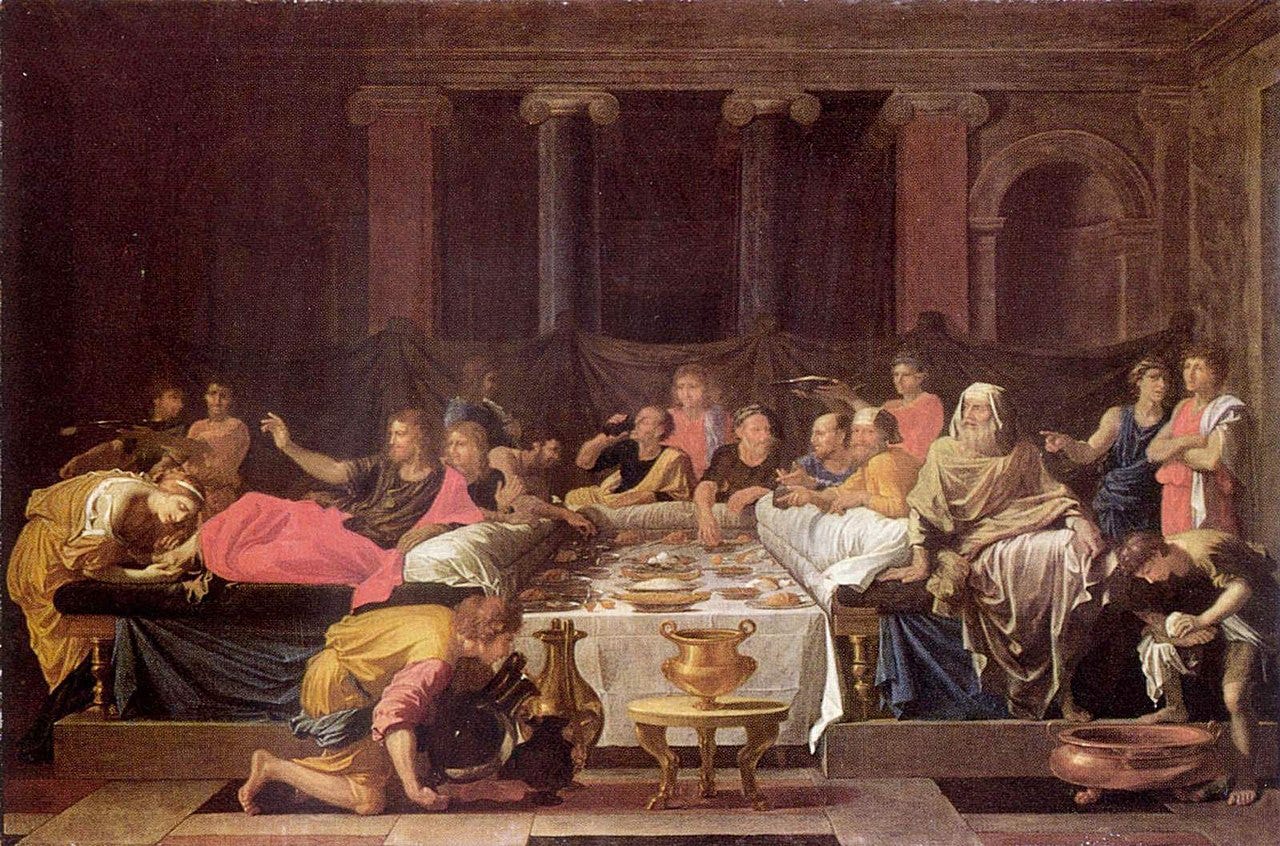

In 1665 the great baroque sculptor and architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini was called to Paris by the “Sun King”, Louis XIV. He was a favourite of Pope Alexander II for whom he had designed the grand colonnade enclosing the piazza in front of St Peter’s in Rome. Now he was to design a new façade for the east wing of the Louvre. Ultimately Bernini’s plans were never realised and the only work to be produced from the visit was a bust of the king which is now in Versailles. There remains, however, an interesting record of Bernini’s stay in the diary of the king’s steward, Paul Fréart de Chantelou who was Bernini’s guide. It was this interaction which led to one of the most remarkable passages of the diary. One day Chantelou invited Bernini to his house and showed to him his most prized possession: a series of paintings of the seven sacraments which he had commissioned from Nicolas Poussin. The diary records Bernini’s reaction. The paintings were hung behind curtains. The great artist first drew back the covering from Confirmation (Figure 2). He studied the scene depicting a moment from the early days of the church: the huddled figures in togas of the purest colours stand solemnly in the dark, saturnine interior of the catacombs beneath the city. Light comes from flickering oil lamps. It is the eve of Easter and the Paschal candle is being lit. Beneath this is the priest and a kneeling figure dressed in a vermilion robe. It is the moment of confirmation, and the kneeling man is being anointed. Bernini drew back and reverently whispered: “What Piety! What Silence!”. One by one Bernini looked at the paintings. When necessary, they were brought to the window for light. Looking at Extreme Unction (Figure 1) (the moment of receiving the last rites) Bernini got down on his knees and changed his glasses from time to time to see the picture better. He said the effect of it on him was “like a great sermon”. He praised Poussin’s genius and knowledge of antiquity and concluded by saying to his companion: “Today you have caused me great distress by showing me the talent of a man who makes me realize that I know nothing”.

Nicolas Poussin was a Frenchman born in Normandy at the end of the sixteenth century who came to work in Rome aged about thirty. In the 1630s he established himself as a painter of relatively small works for a group of patrons who were not of the first rank of Roman society and most importantly among whom was Commendatore Cassiano dal Pozzo, secretary to Cardinal Barberini. It was for him that Poussin painted a first set of the seven sacraments begun in 1638. In 1640, at the request of the king and Cardinal Richelieu, he returned to France for an unsuccessful two-year stay. He came back to Rome where he remained until his death in 1665. His time in Paris was not entirely wasted as he was able to acquire new patrons, including significantly Paul Fréart de Chantelou who had accompanied him on his journey from Rome to Paris. It was then that Chantelou must have seen Poussin’s seven sacraments in Rome, and he commissioned another version of these, but Poussin disapproved of copies and decided to remake the series over again.

It is this second set which belonged to Chantelou, were seen by Bernini, and have come today to be in the Scottish National Gallery on loan from the collection of the Duke of Sutherland. This gives them an advantage over the first set, one of which was destroyed, and the others are scattered across England and America. Only the second set can be viewed together in entirety as intended. They are immediately impressive. Poussin designed his works with a close and careful “reading” in mind, but nevertheless the overall effect of the whole cannot be understated. The set is united by its scale, the scale of the figures, the tones of light and dark and the simple display of primary colours. It is amazing that Poussin was able to achieve this unity given that he sent the paintings off one by one and never saw all together. On walking into the room where they are kept the effect on the viewer is dramatic. One is aware that serious and weighty matters are under discussion; an appropriate tone for depictions of the sacraments: spiritual and physical moments at which God’s grace is visible. These moments are extreme unction, confirmation, baptism, penance, ordination, the Eucharist and marriage.

The air of solemnity is even greater in the second set than in the first: the figures more static, the gestures more deliberate. The scenes are pervaded by a sense of divine calm. This calm is partly imbued mathematically, by the paintings being arranged symmetrically around a central figure or architectural feature.

The first two canvases Poussin painted: Extreme Unction and Confirmation depict anonymous members of the early church while the remaining five are scenes from the story of Christ’s life. Extreme Unction is taken to be an early Christian soldier, his arms hang on the wall behind the bed. Lit by the faint light of a window, candles and the reflected gleam on the shield, the dying man is anointed by the priest. The priest is the central figure around whom the composition turns and on whom diagonals converge in an X. These lines are also to be found in Baptism (Figure 3). Poussin’s method of painting was to work out the design by creating a diorama with wax figures in a box, from which he could work out the positions of the figures and the lighting which he could control. To study the folds of drapery Poussin would create larger models. This method may go some way to explaining the statuesque quality of his work. Another aspect of Poussin’s work was his theory of modes to determine the mood of the painting. This he derived from music: Dorian was sombre and serious, Phrygian was joyful, Lydian melancholic. Maybe this can be seen in the sacraments. Extreme Unction, Confirmation and Eucharist (Figure 6) are dark, barely lit. Ordination (Figure 5) and Marriage (Figure 7) by contrast are a bright panoply of red, blue and yellow expressing the joy and celebration of the moment. The dignity of the scenes can be read in the expressive folds of cloth. They exaggerate gesture and are themselves a form of expression. They are poetic. Bernini was particularly taken with the woman behind the column on the extreme left of Marriage. All that can be seen of her is the folds of her clothing yet in these Bernini read “nobility”.

Looking at Marriage one can see some interesting differences between the versions in Poussin’s first and second sets. In the first set a dove representing the Holy Spirit hovered above Joseph and the Virgin Mary. The second version is more naturalistic. The crowd is calmer and there is less craning of necks to glimpse the significant moment. Peace has fallen over the room, grandly defined by four Corinthian columns. The harmony of the moment is conveyed by the balance of the group and the mathematical pattern on the tiled floor. It is quiet. Beyond the room clouds pass over the city. In his left-hand Joseph holds a flowering branch which refers to Aaron’s rod which had miraculous powers and flowered at Christ’s birth. With his right-hand Joseph gently slips the ring on to Mary’s finger.

Poussin was a master of stillness. His figures have the dignity and aura of classical sculpture. It is no wonder that he was praised by many including Bernini for his knowledge of antiquity. The figures that populate Poussin’s seven sacraments have great feeling to them. They are clearly moved by the moment touched by the numinous. The quiet majesty has created a peace and calm of its own. All that is left to do is to whisper in awe as Bernini did “What Silence!”.