Edward Hopper: Isolation and Melancholy

In Hopper's paintings isolated figures inhabit an abstracted world.

A man sits alone at a café contemplating his coffee. At night in a hotel lobby a woman stares at a blank reflective window. A couple stand silently on the steps of a house looking out into the landscape. There is distance in the paintings of Edward Hopper between the viewer and the painted world and between the figures and their own world. Silence resounds through these stripped back, somewhat abstracted scenes. Figures do not interact, lost as they are in their own minds.

The viewer is at a remove from the world of the paintings. Hopper began his career as an illustrator, but it was an occupation he disliked, and his mature works are far from illustrative. There are no obvious narratives for the viewer to involve themselves in. It is difficult to sympathise with the figures while given no clue to the nature of their situation. Viewers are alienated from the world. They are sometimes cut off from the scene by an artificial horizon as in House by the Railroad (Figure 1) here the train track inserts itself between viewer and subject.

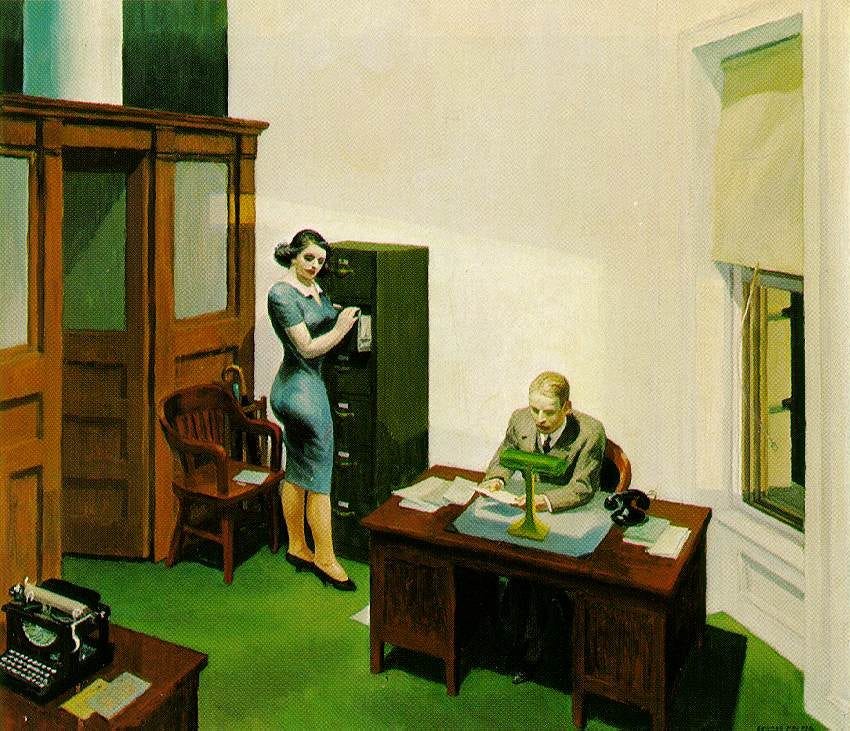

Hopper’s paintings appear as fragments. The world in its immensity extends beyond the picture frame. This impression is given by unusual cropping of the paintings and occasionally by strong horizontal elements as again in House by the Railroad and Manhattan Bridge Loop (Figure 2). The glimpse like nature of Hopper’s works reflects how he found inspiration. Compositions were suggested to him by what he had glimpsed on walks or from train windows. He recalled that Office at Night (Figure 3) had been “suggested by many rides on the L train in New York City after dark glimpses of office interiors that were so fleeting as to leave fresh and vivid impressions on my mind”. There is a voyeuristic quality to Hopper’s work. The viewer almost always intrudes on a figure in a reverie. These figures are sometimes nude or semi-clothed and often the viewer is looking through a window.

In many of Hopper’s works, most famously Nighthawks (Figure 4), windows seal off the world of the viewer from that of the subject. Figures are lost in their own worlds in which we cannot share. Often, they stare out of windows the view through which is hidden from us. The faces of the figures are sometimes obscured. What occupies them is not obvious to us, as in Gas (Figure 5) where the figure stands at a pump.

As well as the estrangement between viewer and subject the painted figures seem alienated from their own world. Look again at Gas. The man stands alone in the dusk. He is on the edge of the light falling from the open door. Behind him, across the road is a dark gloomy wood. The road is deserted, and work has finished for the day. The pumps have served their purpose and stand like solemn totems in the forest. Maybe the man is switching them off: the day’s last ritual. There is something eerie about the setting which is soon to be abandoned for the night. The work is done, and the man no longer belongs here.

Let us look at another of Hopper’s works: Automat (Figure 6). Again, the figure is alone. The woman sits looking into her cup of coffee. She is in an automat, a type of self-service café where food is collected from a vending machine without waiting staff so already there is less suggestion of interaction than one might expect. The isolation of the woman is emphasised by the large blank window behind her. It does not give a hint of the world beyond; it only reflects the lights of the automat giving a tunnel like effect to the darkness.

Even in paintings with more than one person they almost never interact. They are each in their own world. In Nighthawks, in the glass tank like interior of a café figures are gathered around a bar. A man and a woman sit at one end not looking at each other. The woman is looking at something in her hand while in the man’s hand a cigarette quietly burns away. Another man is seated with his back to the viewer. The inertia of the customers is mirrored by the two large silver urns which inanimately sit next to them at the bar. The only active figure is the bartender who is separated from the others physically by the bar as well as by his uniform and occupation.

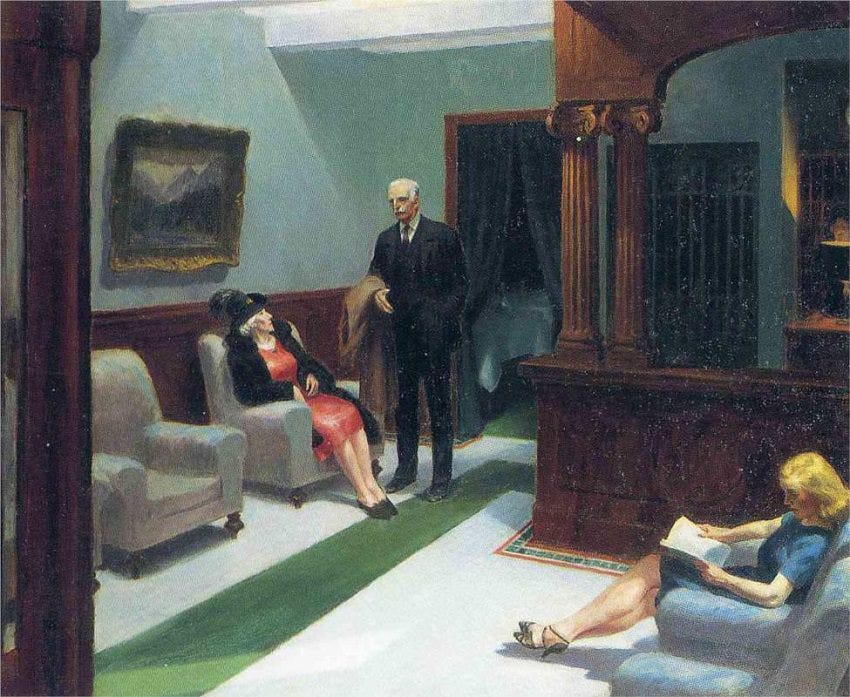

Hopper’s settings are often impersonal. While the moments themselves may be private ones marked by introspection the scene is often in public. The figures sit in cafés, offices, lobbies, theatres, outside. Even when behind closed doors, they are in nondescript hotel rooms.

Alienation is certainly a theme in Hopper’s works. Yet what is its root and what does it signify? It has sometimes been taken to be the dehumanisation of city life, but many of the paintings do not portray cities. Maybe the root of alienation is modern capitalist life more broadly. There are certainly many reminders of this life in the form of railways, shops and advertisements. Indeed, in Hopper’s paintings advertisements offer more communication than the mute figures as in Gas or Nighthawks where the café’s motionless patrons sit beneath a large sign for Phillies Cigars. Companies declaim their messages into the void.

However, there are reasons to believe that Hopper’s figures have not simply become dolls drained by capitalist modernity. Margaret Iversen has more precisely diagnosed their condition as melancholy, a temperament which was traditionally held to result from an imbalance in the body’s four humours, specifically an excess of black bile. This was believed to result in gloom, sadness and isolation. Since the renaissance it is also a temperament which has been associated with genius. As such Iversen has suggested that the withdrawal of Hopper’s figures is partly voluntary. One painting she writes about specifically is Excursion into Philosophy. Here a man sits on a bed, his brow furrowed, lost in thought. Behind him a woman lies naked from the waist down turned away from the viewer. To the man’s left is a window the light from which falls partly on him and creates a patch in front of him on the floor. Next to him on the bed is an open book. Iversen suggests this painting is an allegory of melancholy. In a letter Hopper’s wife Jo states that the book is Plato. It seems perfectly possible that was Edward’s view as well. Plato put the argument that the philosophers must turn their attention away from the fleeting physical world and towards the realm of the forms and ideas. Maybe that choice is shown here by the semi-clothed woman on the left and the window representing abstract thought on the right. In Hopper’s works windows often feature. Figures stare out of them though what they see is hidden from the viewer. The windows relate to the inner lives of the figures. Even when a window is visible to the viewer it is sometimes a scene at night and the window is black. Automat is an example of this. It is easy to imagine the large black window behind the woman as a reflection of her mind. Many of Hopper’s melancholic figures are women, placing them in the long tradition of allegory which includes Albrecht Dürer’s own Melencolia I (Figure 8).

Hopper’s melancholic works may reflect his own life and feelings. He could certainly be described as a melancholic artist. He was a taciturn man who went through long periods of inertia. He produced few paintings each year. It has even been suggested that he was clinically depressive. There is plenty of evidence for being able to see a very personal view of Edward Hopper’s mind in his paintings. He always said he painted not the American scene but his intimate response to that subject. His favourite words of Goethe, which he applied to painting were “the beginning and the end of all literary activity is the reproduction of the world that surrounds me by the means of the world that is in me”.

There is an intellectual air to Hopper’s paintings. They are slightly abstracted. Hopper was interested in the play of light across plain blank surfaces. He dealt in archetypes of America: railways, gas stations and hotels. These elements mean that his paintings themselves belong to the realm of the forms.

Yet is sadness and melancholy all that is to be found in Hopper’s works? There is certainly a feeling of loneliness. But there is a thrill to being alone. Perhaps it is most keenly felt in the city. In his painting Approaching a City tall buildings loom leaving only a small patch of sky exposed. A large blank expanse of wall hides the life of the street, and we are about to enter a dark tunnel on the left. Hopper said he wished to express “the interest, curiosity, fear” of a visitor entering a city by train for the first time. Clearly for Hopper the associations of modern life were complex. Here in cities one can most appreciate the vastness of the world. One can sink into the quiet stillness that may be found even in crowded places. Many of Hopper’s paintings seem to take place at just such a moment. In Nighthawks, Gas and Automat figures pause in silence. Maybe, like the lone man Kierkegaard writes of, Hopper’s figures might say: “one spreads one’s sail, one skims along with the infinite speed of restless thoughts, alone upon the infinite ocean, alone under the infinite sky”. Evident from Hopper’s works is that he, like Kierkegaard knew being alone was complex, but ultimately perhaps Hopper’s figures do feel “how painful, how sad, how humiliating it is to be in this sense a stranger and a pilgrim in the world”. Whatever the truth of this, there is more to Hopper’s paintings than being alone. He once remarked in relation to the understanding of his work “the loneliness thing is overdone”. This suggests loneliness is relevant, but not everything.

To a certain extent Hopper’s paintings simply convey the recognition of other people’s inner life. There may be narratives in the paintings, but they are hidden from the viewer. The faces in Hopper’s works rarely give a clue to what is on the mind of the figures. In many of his paintings window blinds are pulled down to random extents giving no idea of what life may be being lived behind only that there is an individual life, and it is one of accident and chance. An example of this is Early Sunday Morning (Figure 12). Here the archetypal American street is calm and quiet, yet the blinds and curtains give a hint of the lives being lived.

There is beauty in the works of Edward Hopper. There may be loneliness, but there is also calm in their stillness and quietude. In Gas, above the trees, one can see the remains of a sunset and the type of beauty which one feels is displayed for one personally. The Pegasus logo on the sign is leaping into the sky above the trees. Is this whimsical touch an example of the ordinary beauty in the world or does the mixing of the commercial with the mythical merely emphasise the banality of the setting? Can the beauty of Hopper’s painted world be appreciated by the figures which inhabit it? The answer would go a long way to determining the depth of their melancholy or loneliness. Whatever the answer, the atmosphere of Hopper’s paintings is certainly complex, but as he said himself “if you could say it in words there would be no reason to paint”.